Categories: Peptide Finished product, Peptides and Their Dosages

Free (1) 30 ml Bacteriostatic Water

with qualified orders over $500 USD.

(excludes capsule products, cosmetic peptides, promo codes and shipping)

MGF is a splice variant of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1). Research reveals it to have positive effects on tissue growth, wound healing, cardiac repair, and skeletal muscle repair. There is good evidence to indicate that MGF improves muscle repair following injury and boosts recovery times following exercise or injury. MGF may even protect vulnerable tissue (e.g. cartilage) against mechanical stresses such occurs during running, weight training, and repetitive motion.

Product Usage: This PRODUCT IS INTENDED AS A RESEARCH CHEMICAL ONLY. This designation allows the use of research chemicals strictly for in vitro testing and laboratory experimentation only. All product information available on this website is for educational purposes only. Bodily introduction of any kind into humans or animals is strictly forbidden by law. This product should only be handled by licensed, qualified professionals. This product is not a drug, food, or cosmetic and may not be misbranded, misused or mislabled as a drug, food or cosmetic.

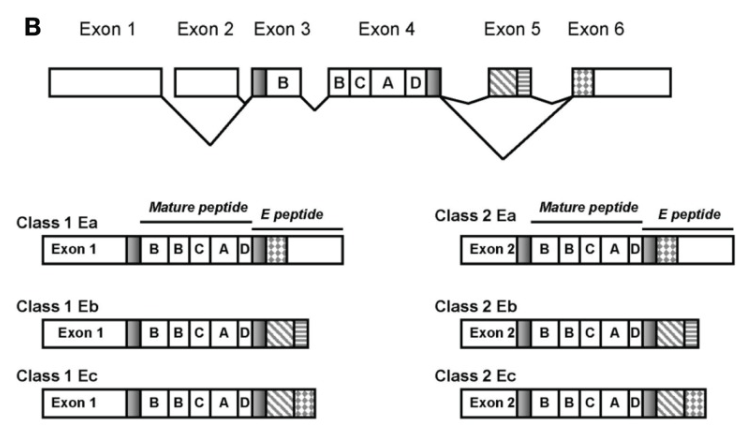

Scientists have known about alternative splicing for some time now. The process refers to the ability of a cell to create mRNA strands in different ways to produce a wide variety of proteins from the same basic DNA sequence. IGF-1 turns out to be on the extreme end of alternative splicing. With six exons and multiple transcription sites, IGF-1 can be spliced into two classes consisting of three major isoforms each (IGF-1Ea, IGF-1Eb, IGF-1Ec) for a total of at least six different proteins. These peptides can then be further modified to produce an even wider variety of alternatives[1].

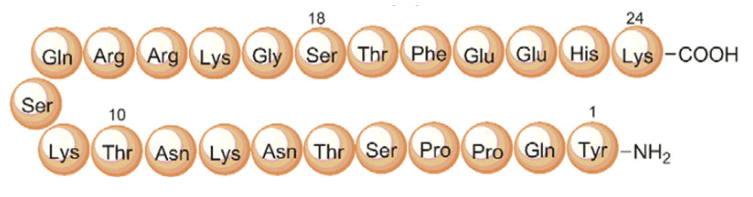

Mechano-growth factor is an alternative name for the IGF-1Eb isoform of IGF-1. It has been shown to play important roles in muscle remodeling, cellular proliferation, and cellular survival. New research suggests that this particular isoform can also activate satellite cells in skeletal muscle, protect neurons, and offset the muscle-wasting effects of aging[3].

The primary role of MGF is in muscle acute repair, particularly after exercise or injury. Research in rats shows that concentrations of MGF increase dramatically following muscle injury and that its presence in muscle correlates strongly with skeletal muscle cell growth and differentiation[3].

As it turns out, the specific versions of IGF-1 that are produced depends on a number of factors. Age, steroid hormones, growth hormone, and other developmental cues all affect how IGF-1 is spliced and the final peptides that are produced. Age, in particular, has been found to have major influence on the expression of IGF-1 isoforms. Young men show now preference between class 1 and class 2 isoforms whereas older men show a statistically and physiologically significant shift toward class 1Ea[2]. The overall significance of this change in terms of obvious signs of aging isn’t clear, but it offers an experimental starting point for understanding better the aging process. There is some thought that MGF supplementation may be able to offset the muscle-diminishing effects associated with aging, though more research is required in this area.

Muscle cell regeneration is mediated by inflammatory cells and the particular signaling molecules they release. Macrophages are especially important in this process and appear to be primary producers of MGF in the setting of muscle cell inflammation. IGF-1Ea (MGF) has been shown to have anti-inflammatory effects, but also prolongs the life of macrophages. The exact significance of this effect has yet to be elucidated, but it is speculated that exogenous MGF administration may boost muscle cell healing rates by affecting macrophages[4].

MGF has been shown to boost hypertrophy and repair of muscle by activating muscle stem cells (called satellite cells). Studies in mice show a 25% increase in mean muscle fiber size after just three weeks of intramuscular MGF injection. Researchers speculate that the peptide could be beneficial in the setting of muscle wasting diseases and that it may also be useful in boosting the effects of exercise[5]. While that latter may seem like an odd recommendation to come from stolid researchers, it underlies the importance of muscle mass in baseline metabolism. It has long been known that boosting muscle mass is a good way to improve basal rates of metabolism and aid in weight loss and fat burning. The ability to improve lean body mass after even moderate exercise could be one part of a multi-faceted approach to the obesity epidemic and the host of medical conditions associated with overweight status.

In the setting of muscle-wasting disease, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), transplanting precursors of muscle cells (called myogenic precursor cells) has been shown to improve dystrophin expression and help offset the effects of some conditions. Unfortunately, survival rates after transplant are low and so the procedure has never been of much therapeutic value. New research in mouse models indicates that MGF can boost survival of myogenic precursor cells and may lead to enhanced transplant success[6]. The benefit of MGF could help make myogenic precursor cell transplant a mainstay of DMD treatment whereas it was once considered a fringe, last-ditch procedure when other options had been exhausted.

Cartilage damage can occur as a result of injury, repetitive overuse of a joint (osteoarthritis), or inflammatory disease (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis). Unfortunately, cartilage does not heal well for a variety of reasons including inadequate blood supply and a dearth of stem cells necessary for substantial regeneration. Research on MGF, however, indicates that the peptide might be able to help overcome some of the inherent limitations of cartilage regeneration.

It appears that MGF helps chondrocytes, the cells primarily responsible for cartilage health and regeneration, survive in response to mechanical stimuli. In other words, in the setting of physical stress on cartilage, MGF boosts survival of the very cells necessary to protect against that stress and repair any damage that it causes. These effects appear to be mediated through several pathways, including the YAP signaling pathway, which boosts chondrocyte migration into cartilage[7].

It is important to note that MGF is not just therapeutic following cartilage injury, but has been found to help prevent injury and long-term disability as well. Mechanical overload is one of the primary causes of disc degeneration in the human spine because overloading chondrocytes causes them to undergo apoptosis (programmed cell death). Research in rodents indicates that MGF can inhibit apoptosis in the cells and thus help to prevent disc degeneration from occurring in the first place[8]. Researchers are actively investigating the use of MGF supplementation to reduce spinal degeneration caused by mechanical overload.

The presence of MGF in the developing brains of mice was demonstrated as far back as 2010 in research that showed the peptide to have neuroprotective effects. Subsequent studies in rodent models have shown that MGF is highly expressed in the setting of brain hypoxia and that it is overexpressed in brain regions where neuron regeneration is taking place. That the peptide has benefit in protecting neurons was finally made clear in a study using a mouse model of ALS (Lou Gehrig’s Disease). Treatment with MGF improves the overall progressive muscle weakness seen in ALS and slows the primary cause of the disease, which is loss of motor neurons[9]. In fact, MGF is significantly better at protecting neurons in the setting of ALS than any other IGF-1 isoform and has been found in regenerating regions of adult brains following global ischemia[10]. There is currently hope that MGF may be used as a treatment to improve muscle function in ALS and protect motorneurons from death[11].

Research in sheep models of acute myocardial infarction (heart attack) indicates that MGF protects heart muscle against ischemia. In fact, the study found that there is a 35% reduction in cardiomyocyte compromise following the injection of MGF and considerable benefit following heart attack[12]. This is a substantial finding because, to date, there have been a limited number of interventions that can reduce the impact of a heart attack while it is happening. Short of stent placement or the administration of clot-busting drugs (which carry the risk of causing life-threatening bleeding), there is little that can be done during the acute stages of heart attack. Most treatment has focused instead on protecting tissue following and event and restoring as much function as possible. MGF is opening new avenues for treating acute MI that could give first responders a real tool that can reduce the impact of heart attack by more than one third. Given that cardiovascular disease is, but far, the largest killer of adults in most developed nations, this finding has the potential for substantial benefit.

MGF is being explored via a number of different research avenues. Right now, the peptide shows a great deal of promise in protecting muscle tissue of all types from a wide variety of insults. This makes MGF a prime candidate for pharmaceutical development and the peptide may serve as the basis for a number of breakthrough treatments over the next decade. Additionally, new aspects of MGF are being uncovered regularly. The peptide is already known to protect neurons and boost cartilage health, so there is a wide area of application for current and future research.

MGF exhibits minimal side effects, low oral and excellent subcutaneous bioavailability in mice. Per kg dosage in mice does not scale to humans. MGF for sale at

The above literature was researched, edited and organized by Dr. Logan, M.D. Dr. Logan holds a doctorate degree from Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine and a B.S. in molecular biology.

Paul Goldspink, PhD is the Principal Investigator and Associate Professor at the Department of Physiology within the Medical College of Wisconsin. The research in Dr. Goldspink’s laboratory is focused on understanding the actions of IGF-1 isoforms in the heart and other tissues. We are investigating the role of IGF-1 isoforms in response to stresses such a mechanical overload, hypoxia, oxidative stress and age in the heart. We have focused on a particular isoform called Mechano-Growth Factor (MGF), which plays a protective role in preventing cell death, preserving contractility and preventing pathologic hypertrophy of the heart following myocardial infarction. We are currently investigating the underlying mechanisms utilizing peptide analogs derived from the E-domain region of MGF which serve as allosteric modulators of excitation-transcription pathways in muscle. Through collaborations we have been able to exploit our findings by developing a technology that combines a microscopic physical scaffold to deliver peptide therapeutics, with the goal of improving cardiac function during the progression of heart failure by using implantable cell-sized “biomimetic devices”. The development of these intelligent drug delivery platforms which we have recently employed in the heart, also have applicability of other tissues and disease states.

Paul Goldspink, PhD is being referenced as one of the leading scientists involved in the research and development of MGF. In no way is this doctor/scientist endorsing or advocating the purchase, sale, or use of this product for any reason. There is no affiliation or relationship, implied or otherwise, between

ALL ARTICLES AND PRODUCT INFORMATION PROVIDED ON THIS WEBSITE ARE FOR INFORMATONAL AND EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY.

The products offered on this website are furnished for in-vitro studies only. In-vitro studies (Latin: in glass) are performed outside of the body. These products are not medicines or drugs and have not been approved by the FDA to prevent, treat or cure any medical condition, ailment or disease. Bodily introduction of any kind into humans or animals is strictly forbidden by law.

PeptideGurus is a leading supplier of American-made research peptides, offering top-quality products at competitive prices. With a focus on excellence and customer service, they ensure a secure and convenient ordering process with global shipping.

CONTACT